(Above: Detail from the cover of Here for the Present: A Grammar of Happiness in the Present Imperfect by Barbara Mossberg — the figure in the window represents the writer; cover art and illustrations by Sophia Mossberg.)

Title: Here for the Present: A Grammar of Happiness in the Present Imperfect

Author: Barbara Mossberg

Publisher: Pacific Grove Books (an imprint of Park Place Publications), Pacific Grove, Calif.; July 2021, 188 pages

Available locally: Black Sun Books (2467 Hilyard St., Eugene; 541-484-3777; blacksunbooks.net); J Michaels Books (160 E. Broadway, Eugene; 541-342-2002; jmichaelsbooks.com)

By Randi Bjornstad

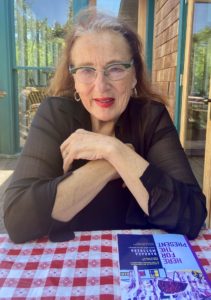

Poet and professor Barbara Mossberg has just published a new book of poetry and prose, oriented around her years as poet-in-residence in Pacific Grove, Calif.; photo by Randi Bjornstad

Poet (and professor in the University of Oregon’s Clark Honors College) Barbara Mossberg has just published a new book of her writings, titled Here for the Present, and if that rings a bell in some long-ago memory — especially likely if you ever were a fan of Beverly Cleary, the prolific writer of books for children and young adults who died in March 2021 less than a month shy of her 105th birthday — that may be the reason.

Mossberg explains all this in the preface to Here for the Present. If, like many readers, you usually skip over the preface in books to get to the real thing, you might want not to do that this time. To begin with, the preface explains not only the book’s title — Here for the Present — but also its relationship to its subtitle, A Grammar of Happiness in the Present Imperfect.

When is the present not a present?

The book itself contains 180 pages of experiences, thoughts, and writings from the several years Mossberg spent as Poet-in-Residence of Pacific Grove, Calif., a small city of some 16,000 people on Monterey Bay just northwest of the city of Monterey. As such, the multiple meanings of the word “present” is an important element in this book, beginning with the confusion of Beverly Cleary’s perhaps most popular fictional character, Ramona Quimby, as the 4-year-old starts her first day of kindergarten.

As recounted by Mossberg, the teacher, Miss Binney, shows Ramona to a chair and tells her to “sit here for the present.” Being a literal child, as most are, Ramona immediately thinks that school is going to be a wonderful place if she receives a present on the very first day and also that she is going to like this teacher very much.

Time goes by, the other children begin playing a game, and Miss Binney asks Ramona if she wouldn’t like to play, too. Ramona says she can’t, because the teacher has said she if she sat there she would get a present, and that’s what she is waiting for.

“Ramona, I’m afraid we’ve had a misunderstanding,” Miss Binney said. “You see, ‘for the present’ means for now. I meant that I wanted you to sit here for now, because later I may have the children sit at different desks.”

That was little Ramona’s first inkling of the complexity and perplexity — and occasional disappointment — of language. But Mossberg uses the child’s reaction to think about a greater meaning.

“To be present, in the way we mean consciousness, to be fully alive, awake, aware, is a present to oneself,” she writes. At the same time, being “here for the present” reminds us that “our own life on earth is temporary. We are living here for the time being, so we should relish the experience as deeply, and consciously, as possible,” she says.

Mossberg published her first book of original poetry, titled Sometimes the Woman in the Mirror is Not You, in 2015 in the form of a chapbook, defined historically as a small paperback containing poetry or fiction.

In contrast, she describes her new volume, Here for the Present, as a “standup memoir” — a gift, if you will — containing a compendium of poems, essays, observations, speeches, and memories drawn from her experiences of travel, teaching, travel-and-teaching, simple domestic chores, the view out the window, health challenges, death in the family, and contemplation of what a museum-of-herself would contain.

And that gets to the subtle meaning of the subtitle of Mossberg’s book, recognizing the existence of the “present imperfect,” a concept which she extends to real life as much as to a grammatical form.

In English, the basic “tenses,” of course, are present, past, and future. However, grammarians subdivide these even further, into as many as 12 combinations that augment the basic three with words such as simple, continuous, perfect, even perfect-continuous. And then there’s the imperfect, which to many poets probably is far more intriguing to contemplate than the perfect.

For example, present perfect generally — perhaps even a bit oddly — refers to something that someone has done in the past but which is no longer happening. Enter the imperfect, which also refers to something that was done in the past but with the complication that it might be something that is done regularly or frequently, so it really isn’t finished after all. Hence the imperfection. And the poetry.

“So here we are, in the present, the here and now, and it’s not yet over,” Mossberg says to explain her subtitle, A Grammar of Happiness in the Present Imperfect. “And while it is temporary, it is also infinite in the moment. So the moment is a gift that keeps on giving as long as we are in the here and now — for the present!”

What she wants to say

“What’s interesting about this book is that the only thing most people have ever read that I have written were food reviews that I did of restaurants for the Monterey Herald when I was poet-in-residence,” Mossberg says, given that much of the rest of her writing has been circumscribed by her academic career.

“In putting this book together, it was such a personal thing, and now people are reading it — and writing me letters and telling me what they read and how they felt about it,” she marvels. “It’s amazing to me, and so moving — I wanted this to be a gift to the community for being able to have that role, and help people value their own experiences in a different way.”

Even though her residency was focused on Pacific Grove, Here for the Present includes pieces reflecting Mossberg’s experiences and thoughts as she traveled to places as far as Helsinki and as near as Corvallis.

She devotes some passages to the mechanics of daily life, such as musing on the transcendence of daily cookery. Many of these thoughts are as intensely personal as they are universal.

Take for example a reminiscence on pages 103-104 in Part V: The Perfect Imperfect of Quantum Happiness, a reverie about a dress Mossberg bought on sale just because she wanted to, even though it probably was meant for a much younger woman, and by then she was over 60, with all the changes that can bring.

Take for example a reminiscence on pages 103-104 in Part V: The Perfect Imperfect of Quantum Happiness, a reverie about a dress Mossberg bought on sale just because she wanted to, even though it probably was meant for a much younger woman, and by then she was over 60, with all the changes that can bring.

“It’s two layers, almost see-through,” she writes. “Beneath is flesh-colored gauze — sewn into the bodice, and then flows free from the neck and arm seams. That’s it! That’s what is going on with this dress — Free! Flow. The top is bright soft red with white flowers. It is so transparent, so skimpy, so flimsy: like a cloud manifests, weightless, this dress flutters when I turn as if there is a breeze ….”

Her children rolled their eyes when they saw it, her husband “shook his head without shaking it.” But despite how inappropriate it might seem, it made her happy, made her feel the way she wanted to feel when she wore it — a gift for herself, not anyone else — at that present moment.

One day, she wears it with pearls to visit her 88-year-old mother, who had suffered a stroke several weeks before and was in hospice care in an assisted-living facility. At the end of the visit, Mossberg kisses her mother good-bye, and the elderly woman, who has not said a word since the stroke, suddenly does: “you. look. pretty.”

“That’s why,” Mossberg ends her little story, “I wear this dress to face, face to face, heaviness, all gravity’s laws, weighted with sorrow, and loss, and fear, in hospice. I wear it, this buoyant excess, this innocence. Good style; good class: tell me it’s an inappropriate dress.”

Looking ahead

During the process of completion and publication of Here for the Present, Mossberg and her family — husband Christer and daughter Sophia — had to cope with the death of son-and-brother Nicolino to illness early in 2021. The book is dedicated to him: here when this book began, an infinite presence, present, she writes.

And it is the ongoing gift of Nicolino’s spirit, talent, and curiosity, Mossberg says, that may provide the impetus for her next artistic endeavor, which she gives a working title of “museums, monuments, and installations.”

“He lived in my family’s longtime home (in southern California), and he was like the curator of a museum,” Mossberg said. “He collected things, he restored things, he arranged things symbolic to the family everywhere in the house. My idea now is to look at each object and write a catalogue about him and his ‘artifacts’. I’m thinking about the best way to do this to honor him and his presence and his attention to the family history.”

His efforts made her stop and think about what she — and everyone else — might want to see in a “museum-to-self” that truly reflects their lives, both the present in which they lived and also their continuing presence in the world as represented by sharing the belongings and surroundings important to them.

It raises so many questions, she says, some serious, others whimsical: What would it look like on the outside? What would the statue be? What would be included on inside?

In her own case, “Where would my ashes want to be, maybe in a theater where I love to be watching, writing, acting? In a London cab on the way to a performance?” she quips.

“But what about all the books I love, the journals, the art, the pots and pans, all the things that show who I was when, where I was when, and what was going on in the world?” she says more seriously. “Nicolino has made me think of all these things. I feel they all tell a story. Everyone has a story.”

In her own “museum-to-me,” the objects would include a gift presented to her on her birthday in early August, a gift in her own present that so intuitively discerned the mother-daughter relationship that she says she will never forget it.

“Sophia knows how much I always have loved red-checked tablecloths — and clothes,” Mossberg said. “For my birthday, she gave me not only a red-checked tablecloth — she also gave me a red-checked dress to match.”

Definitely a present for the present, and a cherished artifact for her personal “museum-to-me.”

A “museum-of-self” for poet Barbara Mossberg would include a recent present of a red-checked tablecloth and dress from her daughter, Sophia; photo from Facebook