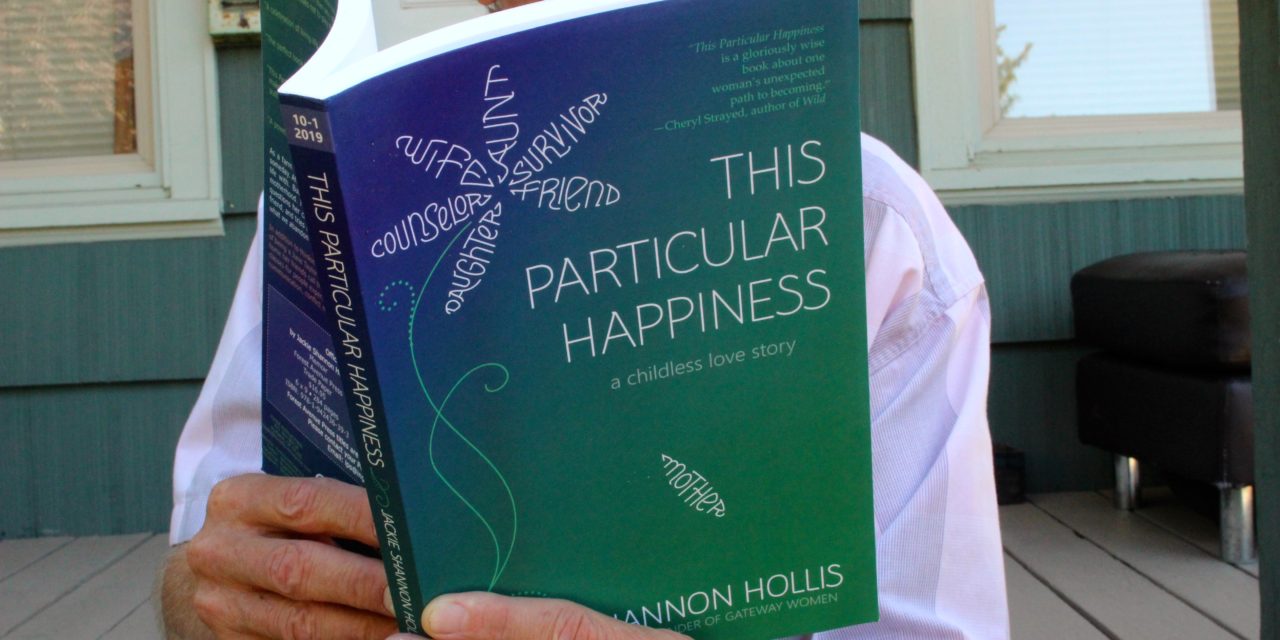

Title: This Particular Happiness: A Childless Love Story

Author: By Jackie Shannon Hollis

Publisher: Forest Avenue Press (Portland)

Available locally: Tsunami Books, 2585 Willamette St. (541-345-8986)

By Daniel Buckwalter

From silence grows weeds, and they choke the life out of love.

It took a couple of readings of This Particular Happiness: A Childless Love Story by Portland writer Jackie Shannon Hollis, followed by her talk at Tsunami Books in Eugene early in October to promote the book, for me to comprehend fully the dynamics of Hollis’ choice not to have children.

I confess, none of my siblings have children. Neither do I, and I know professional women who have not had children. Professional women I have known who gave birth often waited until their late 30s to start a family. I have seen this as the rule. If I thought about it at all, I shrugged.

So it was with some trepidation that I came first to the memoir, then to Hollis’ talk at Tsunami with her best friend, Eugene artist Amy Isler Gibson. I was missing something, but what?

There is community, from family to settled towns. There is work and clubs. They shape and define us, yet do these communities stifle us in our growth and force us to choose among ambition and obligation?

This brings us to Hollis, who is now in her 60s, and her memoir. The author was raised in the village of Condon, Oregon, the seat of Gilliam County with a 2010 Census population of 682. It may have a couple of stop signs. I imagine a family-centered town. Hollis’ mother had four children by the time she was 24.

From that small pond, Hollis first stopped in Eugene for a total of nine years, attending Lane Community College and the University of Oregon. After 1985, she moved to Portland and Portland State University. She has a master’s degree in social work and now lives in west Portland.

Navigating big city life was a challenge. There were dates and boyfriends, a sexual assault and a marriage that ended in divorce. She met her current husband Bill — the love of her life — in 1990 and married him three years later. Always, there was her ambivalence, to say the least, about having children.

In addition to that was Bill not desiring children at all and Hollis meeting and becoming best friends with Gibson, an artist with a love of books. The two traveled to book stores throughout and grew close.

This is where Hollis’ story becomes interesting to me. Both women were young when they met and not interested in children until Gibson became pregnant with the first of her three now-adult sons. Everyone’s world turned upside down.

By itself, that’s not surprising. How could it be anything else?

But it stirred within Hollis the “sadness of not being part of the club.” She writes glowingly of Gibson’s pregnancy, how Gibson looked radiant, of seeing the firstborn sleeping and the quandary she felt about losing her friend to a duty, obligation, and love that is deeply embedded in American culture. In return, Gibson spoke at Tsunami of feeling like “a cow.”

Worse, it led Hollis to pull a curtain on the relationship. She and Gibson would not speak or see each other for 17 years. Neither could put a finger as to why. Hollis simply writes that she felt a “shifting, growing distance” in their friendship.

At the Tsunami talk, Gibson unveiled four pieces of art to accompany Hollis’ memoir. My favorite was No. 2, Scared To Go To Portland. Think Edvard Munch’s famouso Scream, though more muddled. Gibson was afraid to go to Portland during this time for fear of seeing Hollis, though no one understood what the fault lines were.

Seventeen years later, though, Hollis put a mirror up to herself and drew the courage to send Gibson a message via Facebook. The reply was swift.

“I was pissed,” Gibson declared at Tsunami.

Hollis stood still and listened. At the Tsunami talk, Gibson praised her friend for not retreating from the anger. Through emails, the thaw lessened and a new bond was forged.

This is not say that the relationship with Gibson dominates the entire memoir.

There are memorable chapters of Hollis’ mother as well as other friends and acquaintances. Always, there were the questions: Do you have children? Why not? They all cut to Hollis’ heart and comprise this complicated memoir.

This Particular Happiness is written in short, digestible chapters that are heart-wrenchingly honest. If today I can look at a childless professional woman in American society and shrug, it’s because of pioneering women like Jackie Shannon Hollis — women who learned to love and be loved as they wish.

Don’t read it with trepidation.