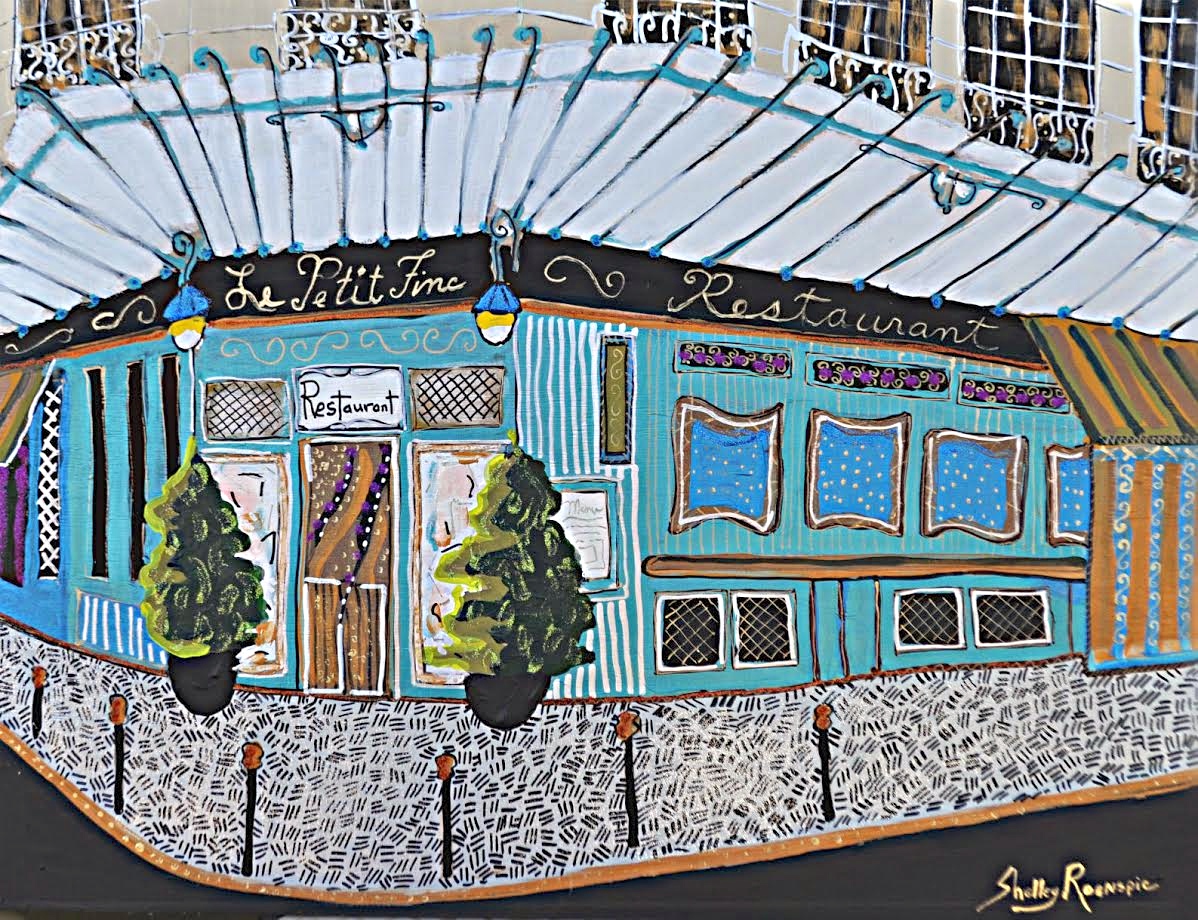

(Above: One of a series of paintings of Cape Blanco done in January 2020 by Eugene artist Marco Elliott)

By Randi Bjornstad

Marco Elliott is a real fan of plein air painting — creating artwork in the great outdoors — and his latest series from a couple of months ago comes just in time to offer a welcome glimpse of nature to people housebound by the still-growing coronavirus pandemic.

“Quite a few of my pieces are painted outdoors while I am struggling with the weather,” Elliott admits. “Sometimes there are signs of raindrops dribbling on my paintings.”

That’s partly because he prefers to work in gouache — an opaque watercolor made of pigment ground in water and thickened with a gluelike material — rather than oil or acrylic.

“So it’s water-based, but still not waterproof,” he said. “Sometimes I can’t completely finish something in the open air because of the weather.”

Marco Elliott’s paintings often have explored his early life in France, above, as well as his affinity for the Oregon coast; photo by Paul Carter

That’s the case with some of his Cape Blanco paintings, which he either has to leave as-is or continue working on in his home studio in Eugene, because Cape Blanco, near Port Orford on Oregon’s south coast, has a fairly harsh environment, especially in winter.

It’s the westernmost tip in the state of Oregon, and it’s also the farthest west in the lower 48 U.S. states except for Cape Alava in Washington State.

“I went to Cape Blanco in January with a friend from Alaska, and we stayed in a cabin in a campground,” Elliott said. “We went out near the lighthouse at the end of the road where there’s a parking lot exposed to wind, and neither of us had ever experienced a wind that strong — you had to keep hold of the car door or it could be blown off, and you had to lean hard into the wind even to walk.”

The next day, Elliott had a chat with a park ranger, who said the wind had been about 60 mph, “but that it wasn’t anywhere near the strongest on record.”

In fact, extreme weather records indicate that during the Columbus Day Storm in 1962, sustained winds at Cape Blanco reached 150 mph, with gusts to 179 mph.

“When I go somewhere like Cape Blanco, I don’t try to plan a series of paintings that I want to do, I just go and see what’s there,” Elliott said. “Like this time, I just wanted to forget about all the problems we’re facing in this country and find a beautiful spot that would really talk to me.

“Then I try to absorb what I see and let it filter through my nervous system,” he said. “And after that, I see what happens when I put it on paper.”

At some point, an artist painting in nature has to decide which instant he or she wants to preserve.

“Every once in awhile, you get a little ribbing from Mother Nature,” Elliott acknowledges. “One minute I think I really have something, and then like a little wink, the light changes, and I have to decide, do I want to get this?”

It all depends on the painter’s expectations, “because if my goal is simply to capture fleeting moments, I probably should change mediums and get into photography,” he said. “So sometimes I finish something in one sitting, and other times, if I know I will need more than one sitting, I concentrate on the landscape and the vegetation that don’t change as much and leave certain things like sky or ocean unfinished until I come back.”

It all depends on the painter’s expectations, “because if my goal is simply to capture fleeting moments, I probably should change mediums and get into photography,” he said. “So sometimes I finish something in one sitting, and other times, if I know I will need more than one sitting, I concentrate on the landscape and the vegetation that don’t change as much and leave certain things like sky or ocean unfinished until I come back.”

In the end, the painting “is only the marks I put on paper,” Elliott said. “When it comes to portraying nature, there’s really not one simple truth, so I am interested in doing my best to grasp one part of nature’s truth.”

In that sense, art can be something akin to a contact sport. In a 2017 interview with Eugene Scene, Elliott likened it as a challenge to the artist “to capture fleeting changes of light and movement with an adrenaline rush akin to a batter waiting for a perfect pitch or a kayaker fighting through rapids.”

Elliott’s fascination with painting began early in life in France, where he was born and lived for 35 years. Once back in the United States, he continued his art — plein air and murals — as he taught art for 22 years in the Los Angeles School District before he and his wife, Joann Carrabbio, also a painter, relocated to Oregon.

One of Elliott’s perennially favorite spots to paint is in the wetlands area of Sutton Beach north of Florence.”To get there, you have to climb across on a log bridge over a creek, so it’s not someplace a lot of people go,” he said. “But I find it a rewarding place to paint.”

Elliott describes his landscapes mostly as somewhere between representational and abstract, in part “because I tend to be neurotic when I find myself getting really fascinated by details of plant life or rock formations,” he said. “So I try to make myself get a little lazier and find shortcuts that allow me to show nature in a more stylized way.”

That’s particularly important in plein air painting, “especially if it’s really cold or rainy, when I don’t have the time or energy to pursue a lot of detail,” he quips. “Sometimes, you really just need something else more, like beer or hot chocolate.”

A maquette — a preliminary model or sketch — that artist Marco Elliott did for a mural in his home town of Cannes, France, where he grew up and lived for 35 years. He always has gravitated toward portraying coastlines and landscapes.